Approach

Combining Methods of Control

Gamepad hardware and interaction designs have been solidified and standardized across many genres of games, such that most commercially available gamepads can be interchangeable for most use cases. Motion based input devices, however, are much more differentiated. Virtual reality systems use a mix of wearable inertial measurement units and computer vision to implement a nearly seamless mapping between the human player’s body motion and their avatar. These are typically proprietary hardware devices designed for use only with their respective hardware ecosystems. Computer vision based approaches allow for more options. There are many open source implementations of body tracking software that can be used with many kinds of cameras, even common laptop webcams. The Microsoft Kinect device is a purpose built motion tracking camera with the added ability to capture depth data about the scene using infrared sensors. This allows for more accurate body tracking than a single standalone webcam might be able to offer.

Hybrid Control Schemes

This body motion input can be seen as a layer on top of more traditional interaction mappings presented through a gamepad controller. Moving the avatar around the virtual space, or orienting the camera are typically done with a pair of analog joysticks, a common feature on most commercially available gamepads today. Buttons are often used to trigger more complex functionality, like jumping and climbing platforms or opening doors. User interfaces and menus are typically interacted with a combination of directional inputs and button presses. The body input layer can be activated for specific interactive moments which might require more control over the avatar body, or even just for freely expressing via avatar body motions.Currently, a paradigm of pre-defined animated sequences called “emotes” has become a standard method of expressing via avatar body motion in multiplayer games. This paradigm already switches control of the avatar body away from the gamepad to a separate system. In this case the system is an automated system moving the avatar based on previously authored animation data. With this proposed hybrid interaction system, this emote moment could simply switch control to a full body tracking input to let a player effectively author their own emote animations in real time.

Inspiration

In looking for a metaphor to design towards, the animated show Avatar: The Last Airbender seemed to be a good choice. The world is based around martial arts practitioners who cast spells by performing kicks, punches, flips, and many body movements to cast spells of four different elements; Earth, Water, Fire, and Air. The simple elements also lended themselves to a rock-paper-scissors style of logic that is often employed in games such as the hugely popular Pokemon to determine which spell type can defeat or counter another spell type. However, as design moved forward, the martial arts angle seemed to complicate matters in directions that were less about moving the avatar body and more about moving the human body itself.

In looking for a metaphor to design towards, the animated show Avatar: The Last Airbender seemed to be a good choice. The world is based around martial arts practitioners who cast spells by performing kicks, punches, flips, and many body movements to cast spells of four different elements; Earth, Water, Fire, and Air. The simple elements also lended themselves to a rock-paper-scissors style of logic that is often employed in games such as the hugely popular Pokemon to determine which spell type can defeat or counter another spell type. However, as design moved forward, the martial arts angle seemed to complicate matters in directions that were less about moving the avatar body and more about moving the human body itself.

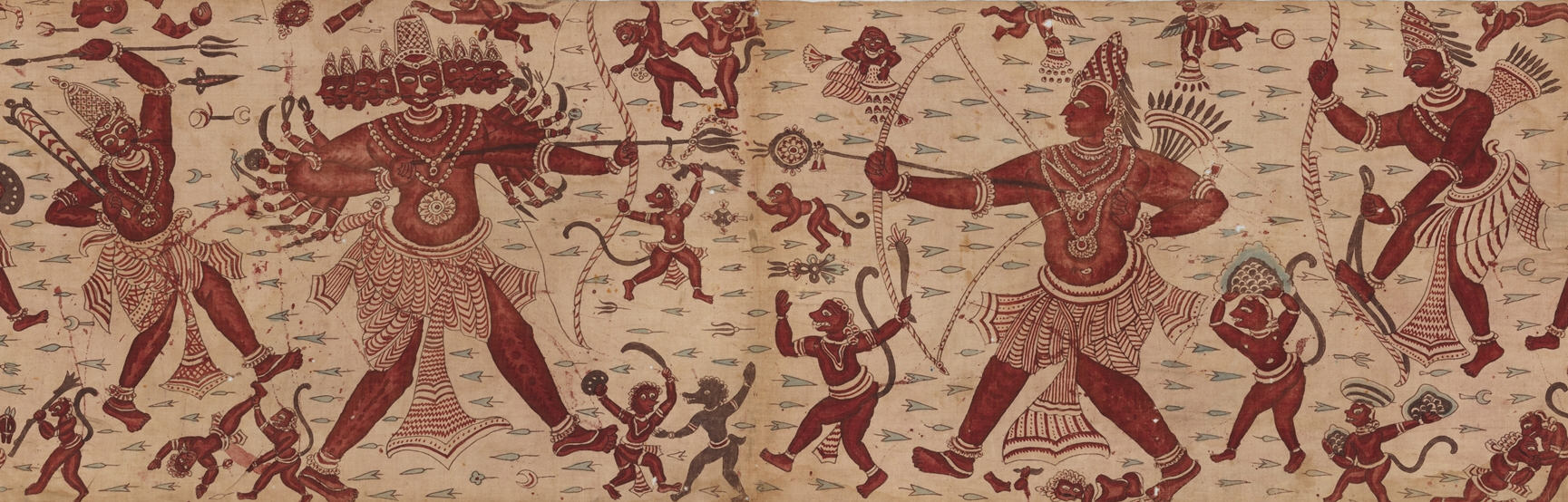

Departing from martial arts, but focusing on the concept of spells and counterspells, the idea of asthras from Indian mythology seemed apropos. These were magic weapons endowed with power by various deities, often in the form of a powerful arrow fired from a bow. Asthras show up in many different stories from Indian mythology. While some were meant for destructive power, others were used for protective purposes, and often different kinds of astras were used to counteract an opponent's asthra attack. One iconic example from the epic Ramayana is the final battle between the main protagonist, Rama, and the villain of the story, Ravana. The two powerful warriors were locked in combat, firing arrows from their chariots across the battlefield at each other.

Following along with the metaphor of the asthras, a player can recognize what type of spell their opponent is firing,

and can determine what type of spell to use to neutralize the arrow. A rock-paper-scissors paradigm will be used to

determine which element counters which other elements.

Following along with the metaphor of the asthras, a player can recognize what type of spell their opponent is firing,

and can determine what type of spell to use to neutralize the arrow. A rock-paper-scissors paradigm will be used to

determine which element counters which other elements.