A Study of Wearable Interfaces for Historic Reenactment

Designed by Candice Butts under supervision of Dr. Michael Nitsche

Human-Computer Interaction, MS 2022

I believe that understanding the past is essential to better perceiving the present and future.

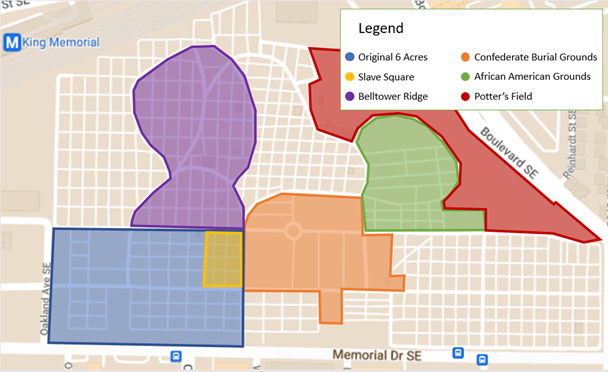

In the years following the American Civil War, Atlanta, GA became a boomtown, drawing thousands of new residents and quickly filling the city's only public burial grounds. In 1877 the Atlanta City Council voted to clear a field within Oakland Cemetery. The field, sitting on a ridge then popular with the city's wealthiest residents and lying across from the Confederate Memorial Grounds, was cleared and each newly approved lot was sold for no less than $50, a premium (Thomas, 1966).

But the material goods Oakland and the city gained could not atone for what was lost morally, for the field was not empty. Known as Slave Square, the field served as the burial space for enslaved and free Black Atlantans before and during the Civil War. With the April 2, 1877 vote, the city of Atlanta removed the “bones and bodies” of these Black Americans from the coveted lot and reinterred their remains in Potter’s Field at the rear of the cemetery (Thomas, 1966, p. 45).

Map of Oakland Cemetery. Enslaved and free Black individuals were disinterred from their original resting place in Slave Square and moved to plots in the African American Grounds and Potter’s Field.

This project examines the value of custom-built wearable interfaces for historic reenactment, particularly for difficult cultural heritage topics. It includes the design of a special historic tour of Oakland Cemetery, which uses a custom-built dress and other novel interfaces to engage with visitors along the tour. Its central research question is: How could a prop or a device help the audience to feel more connected to the cultural heritage presented? This idea will be explored through the context of a Digital Humanities-informed HCI project for Oakland Cemetery, a historically significant site located in Atlanta, Georgia.

"Oakland Cemetery" by davidkosmos is marked with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Problem Area

With so much for the eye to behold, and 172 years of problematic history to uncover, which best practices could the cemetery use to tell these stories?

As an educational facility Oakland is aware of its historical role as a “physical manifestation” of the city’s history with racism (Flowers, 2007). In addition to contextualizing the history of Black Americans (particularly in a “liberal” city), this space provides opportunity to explore female-led cultural practices especially in the realm of death culture, racial policies, and gender roles (Janney, 2008). By exploring the African American burial grounds at Oakland, A Study of Wearable Interfaces for Historic Reenactment seeks to better represent the experiences of African American women pre- and post-Civil War and their participation in American cultural norms.

Research

Target Users

Visitors

A Study of Wearable Interfaces for Historic Reenactment seeks to create novel tour experiences for visitors to Oakland while maintaining the character of this historic site. User research conducted by Stantec Consulting Services Inc. revealed special events such as tours and annual programming attracted over 70% of Oakland’s visitors (Stantec, 2018). “Informed tour volunteers,” “stories of the past and history,” and “’feeling the history” were reasons cited for return visits; visitors also expressed a desire for more programing and tour options (Stantec, 2018, p. 15).

Experts

This project seeks to support Oakland in its goal of creating more programing by providing additional tools and methods to aid Oakland’s interpreters. To better understand the needs and perspectives of guides and interpreters, a cultural probe was created for experts in the field of cultural heritage. This cultural probe is a survey with several activities used for insight into the expert’s work and educational methods (Gaver, et al, 1999). The probes consisted of long and short answers, drawing activities, and thought experiments across seven core questions. Ideally, probes would be conducted in person and with physical documents and props to elicit feedback. However, the Covid-19 pandemic placed limitations, therefore, online surveys were deployed the first week of September 2020 through Qualtrics. Five professionals to the call for participants, three completed the survey.

Cultural probe Results

Urgent needs and future hopes for cultural heritage centered on African America history. Experts expressed desires to reveal the reality of African American history to the rest of the nation. By revealing the past, no matter how uncomfortable, cultural heritage work can “help African Americans find their voice” (Cultural probe participant #2).

Personal motivations for cultural heritage work are connected to cultural and personal identity. Truthfully revealing the past gives a voice to African Americans. To engage non-African American audiences, promoting self-identity by finding commonality with, and building empathy for, this marginalized group, is essential (Andrews, et al, 2009).

A sense of place and space is solidified by sensory details and accompanying emotions. Avoiding “flashy” display (Cultural probe participant #3) at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Legacy Museum & National Memorial for Peace & Justice in Alabama provides space for visitors to reflect on the information provided. For example, the Legacy Museum memorialized lynching victims by displaying “the names of men women and children suspended from above” (Cultural probe participant #2).

Methods of audience engagement and immersion are best seen in applying storytelling and performance. Props, storytelling, and dialogue promote audience participation. The presence of reenactors allows visitors to interact with real people. "Audience feedback and interaction lets [experts] know if [they are] connecting with the audience”, or lighten tense moods and build camaraderie between participants (Cultural probe participant #2). Though education may be the interpreter’s goal, including fun or playful elements for guests and inviting input from participants of all backgrounds, make for successful interactions. The target users for this project are twofold: first, to help tour guides and historical reenactors who work at Oakland Cemetery provide a novel interface that offers new means of audience engagement; second, to speak to site visitors and provide an informative and engaging educational tool for them.

Goals

This project builds on the belief that history should be explored within its context, as far as possible. That is why I focus on embodied interaction design to support historical reenactment on site.

Based on expert feedback provided through a cultural probe, a successful design will:

Build audience empathy through storytelling;

Bring enjoyment through playful elements;

Use direct audience interaction to actuate the project; and

Build immersion with props and space.

This project seeks to highlight the history of Oakland’s Slave Square and African American Grounds through the purview of African American women in the waning years of Reconstruction. Oakland Cemetery makes conscious efforts to restore and enhance the historical character of Oakland while limiting disruptive or damaging additions to the site (Stantec, 2018). To achieve the goal of revealing history while maintaining the site, I explored the value of novel custom-built wearable interfaces to support historic tours and reenactment practices. This work is an example of emphasizing cultural heritage through digital means and is important for the fields of Digital Humanities as well as Interaction Design.

Related Work

These projects provide several lessons for potential Oakland designs. Participants appreciate conventions. When asked to perform or engage, users want to be sure that their expertise and previous experiences are appropriate for the task (Honauer, et al, 2020). Participants in this case may be amenable to adjusting expectations if they are provided time to ease into novel designs. Modifications to conventions may also be acceptable in more culturally sensitive areas, such as cemeteries, if they do not commodify emotional and personal culture and practices (Hakkila, et al, 2019). This is not to imply that participants are unwilling to share vulnerabilities and cherished personal memories. As noted in the cultural probe, sharing within a group setting builds comradery between participants. Performance may also provide successful means of exploring sensitive topics by providing “roles” for participants (Demetriou, et al, 2017). In these assigned “roles” participants are provided opportunity to explore the personal narratives and emotions of a “character” outside of themselves (Isbister & Abe, 2015). Group-based projects provide opportunities for more dynamic exploration over solo experiences. Aesthetic immersive elements such as props can either enhance or hinder a project (Isbister & Abe, 2015). Difficult to operate, physically uncomfortable, and thematically inappropriate elements distract from interpersonal dialogue. Successful props meld into the surroundings and build immersion instead of distracting users and spectators.

“Exploring spatial narratives and mixed reality experiences in Oakland Cemetery” (Dow, et al, 2005) produced a drama-based tour of various gravesites, where users could listen to actor-voiced narrations of cemetery residents via a portable audio device.

“Designing an interactive gravestone display” by Hakkila, et al (2019) sought a method of connecting the digital and physical to create interactive in-situ memorials which would enhance gravesite visitation.

Costumes as Game Controllers: An Exploration of Wearables to Suit Social Play (Isbister & Abe, 2015) unfolded as a collaboration between a game designer and a costume designer. Rather than play as a virtual character, the interactors can put on costumes and “become” game characters.

Overcoming Reserve-Supporting Professional Appropriation of Interactive Costumes (Honauer, et al, 2020) created digitally enhanced costumes for a ballet based on dancer and audience feedback and criteria.

Literature Review

The importance of identity and social standing are etched onto the landscape of Oakland Cemetery. The uncertainty of the Reconstruction and post-bellum years provided opportunities for women to carve out unique social and political identities of their own (Janney, 2008). Reconstruction was to be a death knell to America’s previous racist hierarchy, but the influence of White-only organizations like the Ladies Memorial Association limited Reconstruction’s success. Though Black women’s lobbying lacked the overt visibility and funding that White women enjoyed, legal freedom afforded Black women opportunities to partake in nineteenth-century femininity that were denied to them under enslavement (Forbes, 1998). Rather than fully embrace Anglo-American traditions in the Reconstruction era, black women continued to meld Anglo and African traditions and used mourning customs to uphold these values (Henderson, 2008).

To share this history and the values of previously enslaved women, storytelling will be employed. Narrative, with a speculative framework, provides freedom for the designer to interpret historical facts while adhering to cultural norms (Dunne & Raby, 2013). Storytelling can democratize experiences. Participants without lived experiences or the historical background are encouraged to self-identify with the narrative and with those individuals with those lived experiences and historical framework. Self-identification builds avenues for understanding, dialogue, and participation. Through participation, particularly hands-on work, users can gain a deeper understanding of a topic and have a more memorable learning encounter (Kanhadilok & Watts, 2014). Education benefits from play by bringing enjoyment to participants and recreating the past. Technology and novel designs are useful for providing accessible and inventive reproductions which can withstand frequent handling or employ anachronistic elements (e.g., video games of historic campaigns) to engage and inform (Di Franco, et al, 2015).

Design

Rather than a static teaching or experience tool, the final project is an interactive prototype embodying all design criteria highlighted from the cultural probe. This includes the design of a customized tour for Oakland and the design and implementation of tangible interfaces to support the interpreter’s activities. Engagement of the visiting audience will encourage moments of performance, as their response and feedback will become a part of the prototype in action. This will combine with the actual performance, the reenactment component, delivered by the tour guide. All performance will be directly enhanced by the customized interfaces. The earliest design ideations envisioned as single technology enhanced object to tell the story. However, creating a cohesive and immersive narrative tour would benefit from multiple interfaces. Mourning status was most frequently displayed through clothing and jewelry. Since these two elements were held great importance and ritual significance to death culture, and particularly females, textile and non-textile elements feature in the final product.

Tour Details

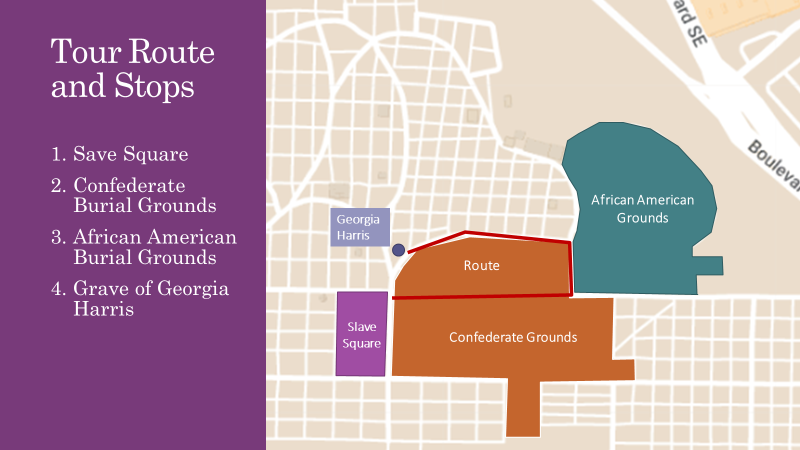

The route loops to four stops.

Four sites within the cemetery are reviewed for this tour: 1) Slave Square, 2) Confederate Grounds Monuments, 3) African American Burial Grounds, and 4) Georgia Harris’s Gravesite.

The interpreter, in character and costume, gives a tour from the perspective of an African American woman living at the end of Reconstruction. The events of the tour are framed to occur on national Memorial Day (regardless of the actual date). The interpreter has taken the opportunity to use this Decoration Day to adorn the grave of a loved-one, and has invited friends (visitors) to participate. This loved-one was originally buried in Slave Square but was disinterred in 1877. The tour stops create a loop as participants walk from Slave Square, through the Confederate Grounds, to the African American grounds, and finally ending a few yards from Slave Square at the grave of Georgia Harris. The content of the tour allows interpreters to take advantage of the geographic placement of each stop, where meaning can be gleaned from the historical racism imbedded into the cemetery (Flowers, 2007).

Stop #1 Slave Square

Archaeological studies of pre- and post-war African American cemeteries and living spaces reveal the ubiquitous presence of small colorful beads (the majority, blue) used for female personal adornment (Stine, et al, 2006). From this research, a thematic connection was made between the traditional beads worn by African American women and Slave Square: invisibility. The historic layout of Slave Square is not visible to current Oakland Cemetery visitors, similarly, the traditional importance of beads to signify Black American womanhood, and the color blue to signify hope and protection for Black Americans is not widely known. In each case, the original use of these elements was obscured by White society as seen in the redistribution of land in Slave Square, and the appropriation of blue in Southern domestic spheres (Henderson, 2014; Parks, 2020). In the process of revealing the history of Slave Square to visitors, we will also reveal African American traditions. The necklace is designed to change from black to blue, initially displaying traditional mourning wear, but unveiling a symbol of protection and positivity within.

Example of Whitbey-style beaded necklace, from Victorian Women of Color: 32 Photos of Beauty In The Age Of Hatred [Photograph]. (n.d.). Flashback.com. https://flashbak.com/victorian-women-of-color-32-photos-of-beauty-in-the-age-of-hatred-31918/

Guide assembling beads. Button-chatelaine belt for audio tour hang from waistband.

The tour necklace design is based on races larger beads like those created in Whitbey, England; regardless of race, these were fashionable additions to a woman’s mourning (and non-mourning) wardrobe (de Carvalho, et al, 2013).

While incorporating jewelry into the project we were encouraged by initial sketches to include the audience in this choice. Rather than produce multiple individual artefacts a single artefact was envisioned for all to enjoy. The necklace is interactive for the audience, assembled from several dormant pieces to create a transformative whole; once completed, the tour guide will wear and activate the device turning several beads from black to blue, providing an illustration of the themes and history covered.

Each beaded strand contains an LED with positive and negative wires attached at the ends to a magnetized snap. The magnets and LEDs are housed within pendants among analog, wooden beads. The pendants are made from modeling clay and molded hot glue. The pendants at the end of each wire snap together, and the magnets help the secure this connection as well as daisy-chain the circuit to the next strand. The device is powered by batteries housed in the guide’s necklace.

Fully assembled beads have turn from black to blue.

Stop #2 Confederate Grounds

The framing of the tour on Memorial Day is deliberate, as the question of who initiated the American tradition is still debated by scholars. The two groups central to this project are 1) Black Charlestonians and 2) the Ladies Memorial Association of Columbus, GA. According to historian David W. Blight the first Decoration Day that the nation would later recognize as Memorial Day, was established by African Americans remaining in Charleston, SC(Blight, 2001). On May Day over 10,000 African Americans gathered to decorate the graves of Union soldiers, hear speeches, sing patriotic songs, and parade around the former racetrack which now served as a cemetery (Blight, 2001). Nine years later a similarly large gathering was held in Oakland Cemetery. On April 27 (Confederate Memorial Day), 1874 “between ten- or fifteen thousand persons” visited Oakland Cemetery to hear speeches, decorate graves, and see members of various auxiliary organizations parade in dedication to the Confederate Obelisk commissioned by the Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association ("Our Atlanta Correspondence, Memorial Day," 1874, p. 4).

"Confederate Obelisk" by George C Slade is marked with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The obelisk was more than a decorative object. Though Southern White women could not vote, monuments they commissioned were representative of the Confederate “patriotism” which continued to “burn with unquenchable fervor” ("Our Atlanta Correspondence, Memorial Day," 1874, p. 4). These projects were supported by White Southern men who benefited from the women’s work as the memorials “provided the platform from which ex-Confederate men could lament their defeat” (Janney, 2005, p. 98). As proxies for depoliticized former Confederate men, Southern White women used their positions in organizations such as the Ladies Memorial Association to uphold racist and white-supremacist ideas. Furthermore, Southern White women softened the North to the Lost Cause Narrative (a sanitized view of Southern antebellum society) by caring for the graves of Union soldiers buried in Southern cemeteries. For example, at Oakland, sixteen Union soldiers are buried among Confederates in the Confederate section (Taliaferro, 2001).

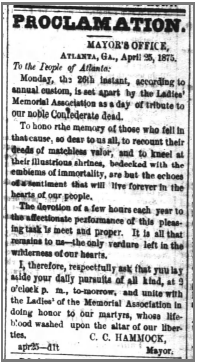

After stepping away from Slave Square, the tour group will make their way towards the African American Grounds by passing through the Confederate Grounds. At the entrance of the Confederate Grounds and to the immediate right is a plaque laid by the Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association. The guide uses the plaque to begin the conversation on Ladies Memorial Association organizations and the history of Oakland’s Confederate Grounds and Obelisk. This portion of the project is an audio tour, like the one created for the African American Burial Grounds and takes inspiration from iterative sketches by creating soundscapes. However, the guide rather than the visitor, is in control. The speaker and Arduino Uno with a WAV shield are built into the interpreter’s costume, hiding the technology. To activate the audio, buttons are built into the costume. These buttons are disguised as everyday objects attached to the interpreter’s chatelaine belt. Three passages were selected for this project. Unique voices and characterization were provided to the text via Google’s Text-to-Speech platform ("Text-to-Speech: Lifelike speech synthesis," n.d.). This free, text-to-speech software was chosen above other options because it produced the most life-like speech. The sources for the three texts are:

Hammock, C. C. (1875, April 25). Proclamation! The Atlanta Constitution, p. 2.

Atlanta mayor proclamation to set aside a day to honor the Confederate dead.

1. A March 1866 LMA member letter to “the press and ladies of the South” (Collier, 1920, p. 20) calling for an annual observance of April 26 as Confederate Memorial Day;

2. An April 1875 proclamation from Atlanta mayor, C.C. Hammock, calling on Atlanta residents to “kneel at [the] illustrious shrines” of the Confederate dead that Confederate Memorial Day (Hammock, 1875, p. 2); and

3. A poem written by a secretary for an Alabama branch of the LMA and inscribed on the Confederate monument located on Capitol Hill in Montgomery, AL (Ockenden & Ladies' Memorial Association, 1900).

Stop #3 African American Burial Grounds

Brooch worn to activate skirt .

After providing some background on the grounds, the guide brings attention to the difference between the African American and White-only decorative practices. While most of the cemetery is covered with stone markings and monuments, the African American section is open, with markers and monuments here-and-there (Henderson, 2008). The two different styles illustrate two different cultural origins, one primarily Western European, and the other primarily West African. What each tradition does hold in common is the use of nature and color symbolism in mourning. The African American Grounds stop gives special attention to the unique blend of African and Anglo symbolic traditions found in throughout African American history.

Like the strand of beads used at Slave Square, visitors are provided an additional jewelry item for the third stop, a brooch. Mourning jewelry were essential accessories to the wardrobe of a woman in mourning. As a “narrative” of the wearer's grief, the brooch, itself, tells a story (Lutz, 2016, p. 221). Visitors are asked to look at their brooch and describe it. The guide asks one participant for their brooch, and once received, the guide puts the piece on, activating the dress and lighting the skirt in a floral pattern. The brooch is backed by a neodymium magnet. Within the guide’s bodice is a neodymium backed button. When the two attract, the button in pushed into the ON position. Wires built into the bodice attach to a string of commercially available LED lights. These lights are arranged into a floral pattern and set into the guide’s skirt.

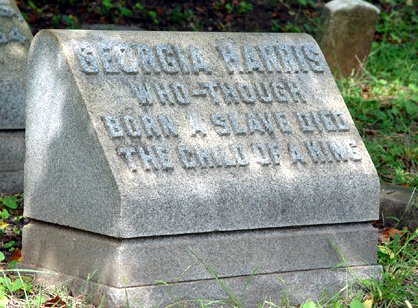

Stop #4 Georgia Harris

Illuminated skirt with floral pattern.

Evening Blues. (2003). Georgia Harris [Photograph]. Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7962013/georgia-harris

Before the tour begins, visitors are presented with black mourning ribbons to wear throughout the experience. Mourning ribbons served as commons option to signify mourning in America since early colonial days (Swink, 2019). The presence of pined black ribbons, arm bands, and widow’s veils were signifiers of the wearer’s status as a mourner (little black dress). Within mourning wear, ribbons and arm bands served as less formal options for individuals wishing to forego the rigors of traditional mourning or seeking more economical options (Swink, 2019).

The concluding stop for this study is the grave of Georgia Harris. Harris, who was formerly enslaved, worked for the Boyd family for 27 years (Black Magnolias: African American Women in Atlanta’s History," n.d.). Like many Black women who called Atlanta home, Harris sought employment in one of the only avenues open to her, domestic service for a White family (Hunter, 1998). We have very little information on Georgia Harris’ life or her relationship with the Boyd family, but the rear of the headstone refers to Harris as "mammy." In the role of “mammy” a black domestic servant could expect to work round the clock tending to the needs of the white family, even more so if she were a live-in employee (Hunter, 1998). We do not know if the work Georgia Harris performed for the Boyd family was similarly as taxing or much more reasonable. Having Harris share the same plot was important enough for Nannie Boyd to petition Atlanta Mayor James L. Key and the owners of neighboring plots for permission since Oakland was racially segregated at the time (Davis & Davis, 2012). But less clear were Harris’ plans for burial. Nannie may have fulfilled Georgia’s wishes with a headstone in the Boyd family plot. Or Georgia may have preferred a traditional African American burial, without a formal headstone and near blood relations, we simply do not know. The question surrounding Georgia’s final wishes are the catalyst to Stop #4’s interaction.

An 1881 mourning ribbon for James Garfield. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian https://www.si.edu/object/mourning-ribbon:nmah_1199440

Mourning ribbons with sound boards created for the tour.

A memorial ribbon pays homage to personalized keepsakes which are made for personal consumption and reflection. The goal is to create a feedback dialogue between the interactor and the dress, itself, for making meaning and teaching. By utilizing spatial, auditory, and visual interactions to make meaning from interactions with the object, users act upon and receive a response from the artefact. In addition to learning about individuals at and history surrounding Oakland, the user is invited to remember these individuals through deliberate action. The act of creating individualized memorials is a slow and thoughtful act, this is further bolstered through meaning making, where the user comes to better understand the elements included in the memorial image by learning about individual women. The struggles and successes of these individuals are highlighted through the lens of Victorian-era memorialization and with a backdrop of Oakland Cemetery.

The Dress

The completed garment.

The tour is placed in time near the end of or after Reconstruction. Taking advantage of the additional space provided in extreme bustle styles, the gown is based on the late bustle era, 1883-1889 (Cramer-Reichelderfer, 2019). The additional space within the collapsible bustle may be useful for hiding technology. Ultimately, the bustle was not needed. But the costume did benefit from a decorative apron to hide LED lights and wiring. The dress was made of contrasting fabrics, a fashionable choice in the late bustle era, but also reflected mourning styles by lacking decorative trim (Bedikian, 2008). The dress is not completely black but uses a dark gray as the primary fabric. Gray, along with white and mauve, were signifiers of half-mourning, where grieving women could acceptably wear more fashionable hair and clothing, attend more lively social events, and widows remarry (Bedikian, 2008). Following “proper” mourning customs, particularly for widows, could necessitate an entirely new wardrobe. Though a boon for manufacturers and department stores, lower-income women would be less likely to fully participate in the minutia of the years-long ritual.

The prototype costume is made from cotton and is light enough that the research interpreter could wear street clothes underneath without becoming overheated. A collapsible bustle was created to support the skirt (pattern by, Stowell, 2013). Pockets attached at either hip housed the Arduino boars and batteries for the LEDs and audio. Strict adherence to historical accuracy in undergarments was not followed. However, a petticoat aided in smoothing over slight protrusions created by the hidden technology. One undergarment which is strongly recommended, however, is a supportive corset. In addition to the bustle, skirt, and apron, the added technology (boards, batteries, speakers, lights, button-chatelaine) are primarily suspended from the waist. A corset will carry this additional weight for the interpreter and provide back support.

Study Design

This project is an IRB approved study. The study aimed to assess the value of different digital storytelling components to the historic tour. Participants were first introduced to the study and its purpose. Then, they were invited to sign the consent form. During the main part of the study, participants followed the researcher over several stations in the Oakland Cemetery. As the tour covers different elements at each station, individual digital interaction designs are activated. At the end of tour, participants completed a primary and secondary questionnaire on the experience. Finally, there was a six-question interview. The entire study took no more than 1 ½ hour. Consent forms and surveys were made available through QR code or hardcopy.

The primary questionnaire is based on three open-sourced studies focused on cultural heritage and usability. “Design factors in the museum visitor experience” (Forrest, 2015) provides a model for gauging how visitors experience different exhibition environments. Mapping Museum Experience (Trundles, et al, 2008) seeks to understand how art, installations, and architecture impact visitors. Finally, only self-reported experts in the field of cultural heritage will be asked to complete a standard System Usability Survey (SUS) (Brooke, 1996). Once the primary questionnaire is completed, participants will be asked to provide demographic data and finally participate in a concluding exit interview. The demographic data asks participants to report their gender, age, education level, and familiarity with Oakland Cemetery. The interview presents six open-ended questions to be asked in a group or individual setting, dependent on the number of tour participants.

Conclusions

Empathy-building stories

Props build the story, taking historical facts and making them come to life through a character. Participants expressed an instant draw to the interpreter upon seeing the costume. Further connection was made with the interpreter’s character through “personalized” items such as the necklace and brooch.

Playful elements to bring enjoyment

Artefacts aid in storytelling, particularly helpful for visual learners. Holding artefacts helped participants to “focus” and listen more intently to the narrative.

Use direct audience interaction to actuate artefact

This tour is unlike any walking tour offered by Oakland, and value is seen in incorporating props, technology, first-person storytelling. The audience was engaged, eagerly awaiting the next reveal.

Incorporate immersion through props and space

Touching and interacting with artefacts makes the past tangible and connects the user to the space. Oakland is the stage for teaching and experiencing, as the geography, architecture, and natural setting illustrate many of the historical facts covered.

Next Steps

Improvements are based on participant feedback and observations made by the research guide. Tests were completed with groups smaller than Oakland’s walking tour groups. Our goal is to explore expanding the interaction to involve more than 20 participants without leaving individuals out of the interaction or becoming too repetitive. Participants expressed desire for more information on the African American Grounds. Additional stops in the African American Grounds, Potters Field, and Slave Square could be added to the tour. Not only will the additions meet this goal, but the tour’s runtime will better match with Oakland's current offerings. To increase guide comfort and ensure easier access to embedded technology, the dress should be redesigned. The skirt would become lighter if LEDs specifically crafted for wearables were included. Unfortunately, these lights must be individually soldered and set into the garment. Including ribbons with their accompanying recordings into a gallery space on Oakland property was not realized for this study. This prospect is still a possibility. However, the voice recording modules used in this prototype inconsistently recorded and replayed audio. A viable solution to this issue needs to be solved before a gallery piece can be designed.

Prototype Video

References

Andrews, R., Mcglynn, C., & Mycock, A. (2009). Students attitudes towards history: does self-identity matter? Educational Research, 51(3), 365–377. doi: 10.1080/00131880903156948

Bedikian, S. A. (2008). The death of mourning: From Victorian crepe to the little black dress. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 57(1), 35-52. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.2190/OM.57.1.c

Black Magnolias: African American Women in Atlanta’s History. (n.d.). Historic Oakland Foundation.

Blight, D. W. (2001). Race and reunion. Harvard University Press.

Brooke, J. (1996). SUS: A 'Quick and dirty' usability scale. Usability Evaluation In Industry, 207-212. doi:10.1201/9781498710411-35

Collier, M. (1920). Biographies of representative women of the south.

Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/biographiesofrep01coll/page/20/mode/2up?q=Atlanta+Ladies+Memorial+Association

Cramer-Reichelderfer, A. L. (2019). Fall of the American Dressmaker 1880-1920.

Davis, R., & Davis, H. (2012). Atlanta's Oakland Cemetery: An Illustrated History and Guide. University of Georgia Press.

de Carvalho, L. M., Fernandes, F. M., de Fátima Nunes, M., & Brigola, J. (2013). Whitby Jet Jewels in the Victorian Age. Harvard Papers in Botany, 18(2), 133-136.

Demetriou, P. A., Pappas, O., & Kampylis, S. (2017). Love Letters–Wearing Stories Told: A performance-technology provocation for interactive storytelling. Body, Space & Technology, 16.

Di Franco, P. D. G., Camporesi, C., Galeazzi, F., & Kallmann, M. (2015). 3D printing and immersive visualization for improved perception of ancient artifacts. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 24(3), 243-264.

Dow, S., Lee, J., Oezbek, C., Maclntyre, B., Bolter, J. D., & Gandy, M. (2005, June). Exploring spatial narratives and mixed reality experiences in Oakland Cemetery. In Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGCHI International Conference on Advances in computer entertainment technology (pp. 51-60).

Flowers, B. (2007). Race, Space and Architecture in Oakland Cemetery. Scapes 6: Public Works, 6, 42-51.

Forbes, E. (1998). African American women during the civil war. Routledge.

Forrest, R. (2015). Design factors in the museum visitor experience (Doctoral dissertation, School of Business, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia). Retrieved from https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:348658

Gaver, B., Dunne, T., & Pacenti, E. (1999). Design: cultural probes. interactions, 6(1), 21-29.

Häkkilä, J., Colley, A., & Kalving, M. (2019, June). Designing an interactive gravestone display. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM International Symposium on Pervasive Displays (pp. 1-7).

Hammock, C. C. (1875, April 25). Proclamation! The Atlanta Constitution, p. 2.

Henderson, D. L. (2008). What lies beneath: reading the cultural landscape of graveyard and burial grounds in African-American history and Literature. PhD Thesis, ETD Collection for AUC Robert W. Woodruff Library. Paper 61. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/9420465.pdf

Henderson, D.L. (2014). Imagining slave square: resurrecting history through cemetery research and interpretation. In M. van Balgooy, Editor, Interpreting African American History and Culture at Museums and Historic Sites (pp. 99-104). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Honauer, M., Wilde, D., & Hornecker, E. (2020, July). Overcoming reserve-Supporting professional appropriation of interactive costumes. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (pp. 2189-2200).

Hunter, T. W. (1998). To’joy my freedom: Southern black women’s lives and labors after the Civil War. Harvard University Press.

Isbister, K., & Abe, K. (2015, January). Costumes as game controllers: An exploration of wearables to suit social play. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (pp. 691-696).

Janney, C. (2005). If not for the ladies: Ladies' memorial associations and the making of the lost cause (Order No. 3169651). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I: History; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I: Social Sciences; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: History; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: Social Sciences. (305380909). Retrieved from https://go.openathens.net/redirector/gatech.edu?url=https://search.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/if-not-ladies-memorial-associations-making-lost/docview/305380909/se-2?accountid=11107

Janney, C. E. (2008). Burying the dead but not the past: Ladies' Memorial Associations and the lost cause. Univ of North Carolina Press.

Kanhadilok, P., & Watts, M. (2014). Adult play-learning: Observing informal family education at a science museum. Studies in the Education of Adults, 46(1), 23-41.

Lutz, D. (2016). DEATH BECOMES HER: A CENTURY OF MOURNING ATTIRE [Review of Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; My Lady Ludlow; Death in the Victorian Family; Death, Dissection, and the Destitute; Mourning Dress: A Costume and Social History; Vanity Fair, by H. Koda, J. Regan, E. Gaskell, P. Jalland, R. Richardson, L. Taylor, & W. M. Thackeray]. Victorian Literature and Culture, 44(1), 217–222. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43923421

Ockenden, I. M., & Ladies' Memorial Association. (1900). The Confederate monument on Capitol Hill, Montgomery, Alabama. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/confederatemonum01ocke/page/54/mode/2up?q=%22heart+shall+be%22

Our Atlanta Correspondence, Memorial Day. (1874, April 27). Weekly Chronicle & Sentinel, p. 4.

Parks, S. (2020, January 14). What the color 'Haint blue' means to the descendants of enslaved Africans. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-haint-blue-means-to-descendants-enslaved-africans

Stantec. (2018). Oakland Alive, Oakland Cemetery Master Plan Update. Historic Oakland Cemetery. https://oaklandcemetery.com/preservation-and-restoration/#masterplan

Stine, L. F., Cabak, M. A., & Groover, M. D. (1996). Blue beads as African-American cultural symbols. Historical Archaeology, 30(3), 49-75.

Stowell, L. (2013, January 2). V346: How to make a Victorian bustle – Pattern and instructions. American Duchess Blog. https://blog.americanduchess.com/2013/01/v346-how-to-make-victorian-bustle.html

Swink, R. C. (2019). Gender and Division of Labor Associated with Dying, Burial, and Mourning in Early America. Fairmount Folio: Journal of History, 19.

Taliaferro, T. (2001). Historic Oakland cemetery. Arcadia Publishing.

Text-to-Speech: Lifelike speech synthesis. (n.d.). Google Cloud. Retrieved April 29, 2022, from https://cloud.google.com/text-to-speech

Thomas, B. C. (1966). Race relations in Atlanta, from 1877 through 1890, as seen in a critical analysis of the Atlanta City council proceedings and other related works.

Trundles, M., Greenwood, S., Wintzerith, S., Tschacher, W., & Van den Berg, K. (2008). eMotion Exit Survey. Retrieved from https://mapping-museum-experience.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/exit-survey-1.pdf