Initial Motivation

In 2018, my great-grandmother passed away, and due to financial and logistical difficulties, my family wasn't able to arrange an in-person funeral service. Without that physical event to commemorate our loss, many family members turned to social media and expressed their grief digitally in the form of sharing pictures and memories. While posting these tributes provided an accessible outlet to mourn with others, we ultimately felt unfulfilled as our personal memories faded into feeds, blurring with political rants and dog pictures. It was clear that social media was not built for the bereaved. Individually, we craved both a private space to reflect on our personal relationship with this person as well as a shared space to sit with others who we knew were feeling the same pain. At the time, there were no suitable options to fill this void.

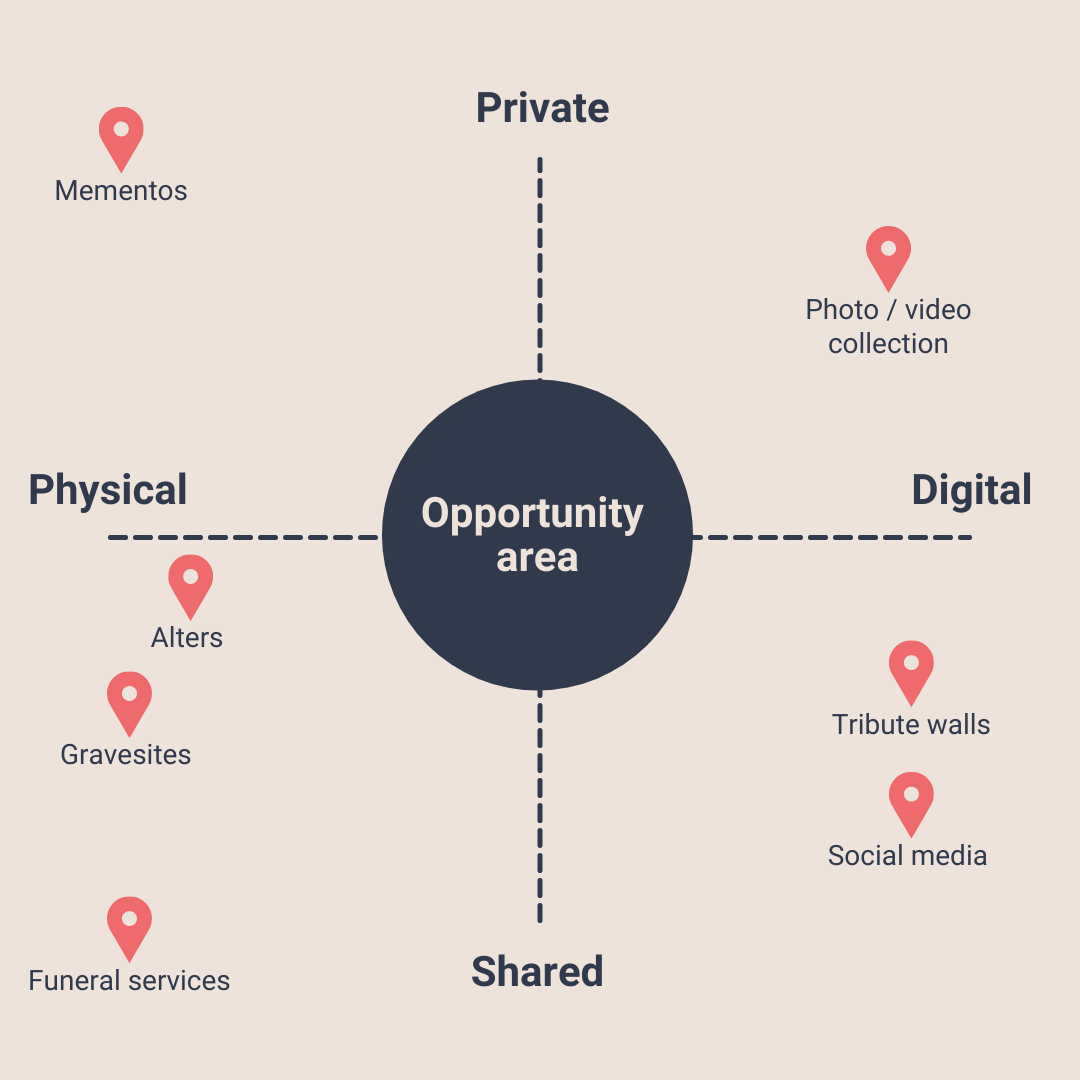

Memorialization Matrix

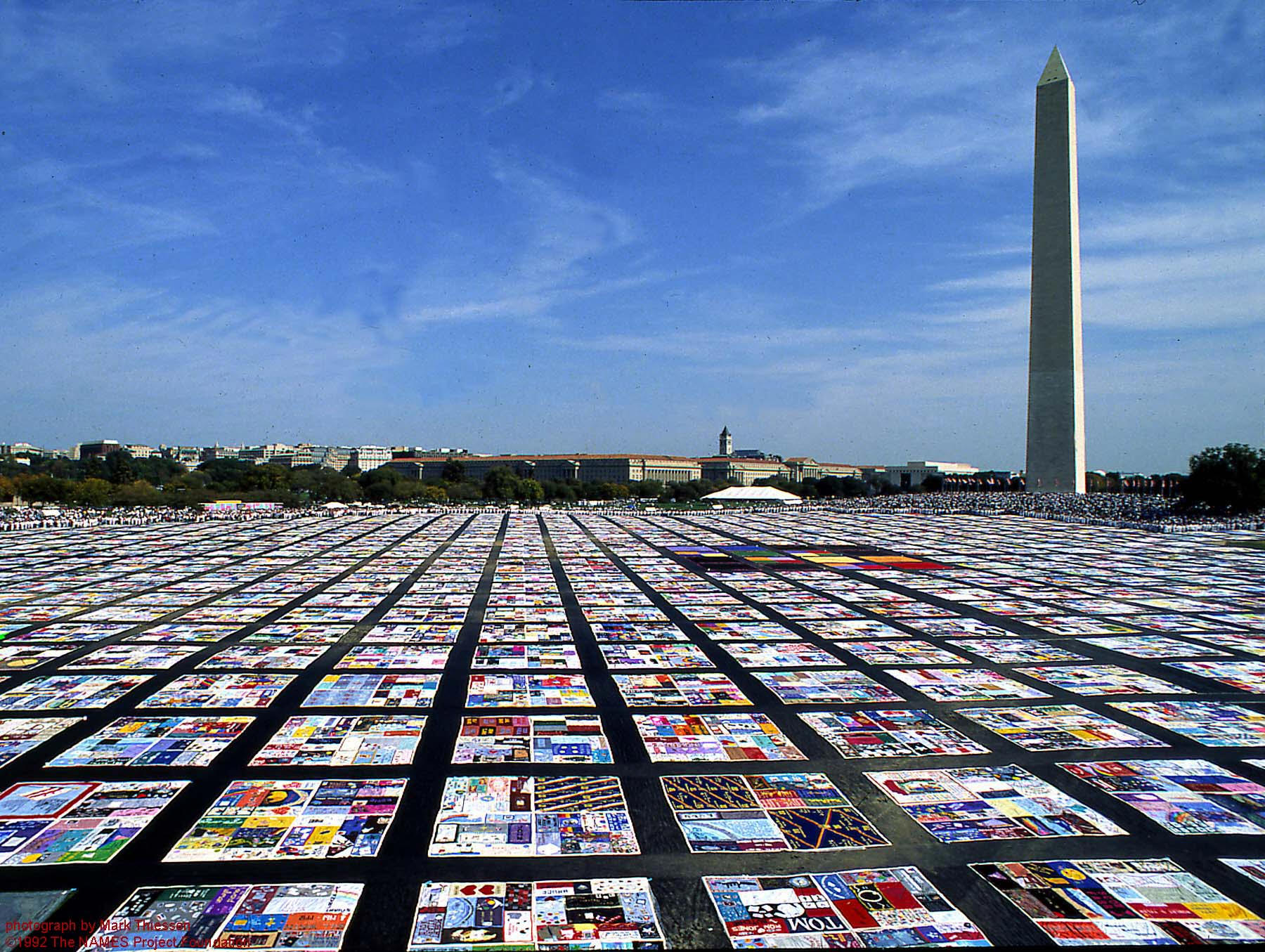

The above experience led to this mapped understanding of contemporary memorialization practices (see right) and opened up an opportunity space that was both personal and shared, to mourn and remember, with two intersecting axes representing the private-shared and digital-physical polarities. While digital practices, like online tribute walls, are accessible for shared grief, they lack an embodied experience and the space for private reflection. On the other hand, physical experiences, such as funerals and cemeteries. exist only in that shared event or space, often lacking the benefit of digital permanence and the opportunity for private memorialization.

Situated in the context of this (working) matrix, my research question is then posed at the intersection of the two axes: How can a memorial experience be simultaneously digital and physical while offering both private and shared space to grieve?

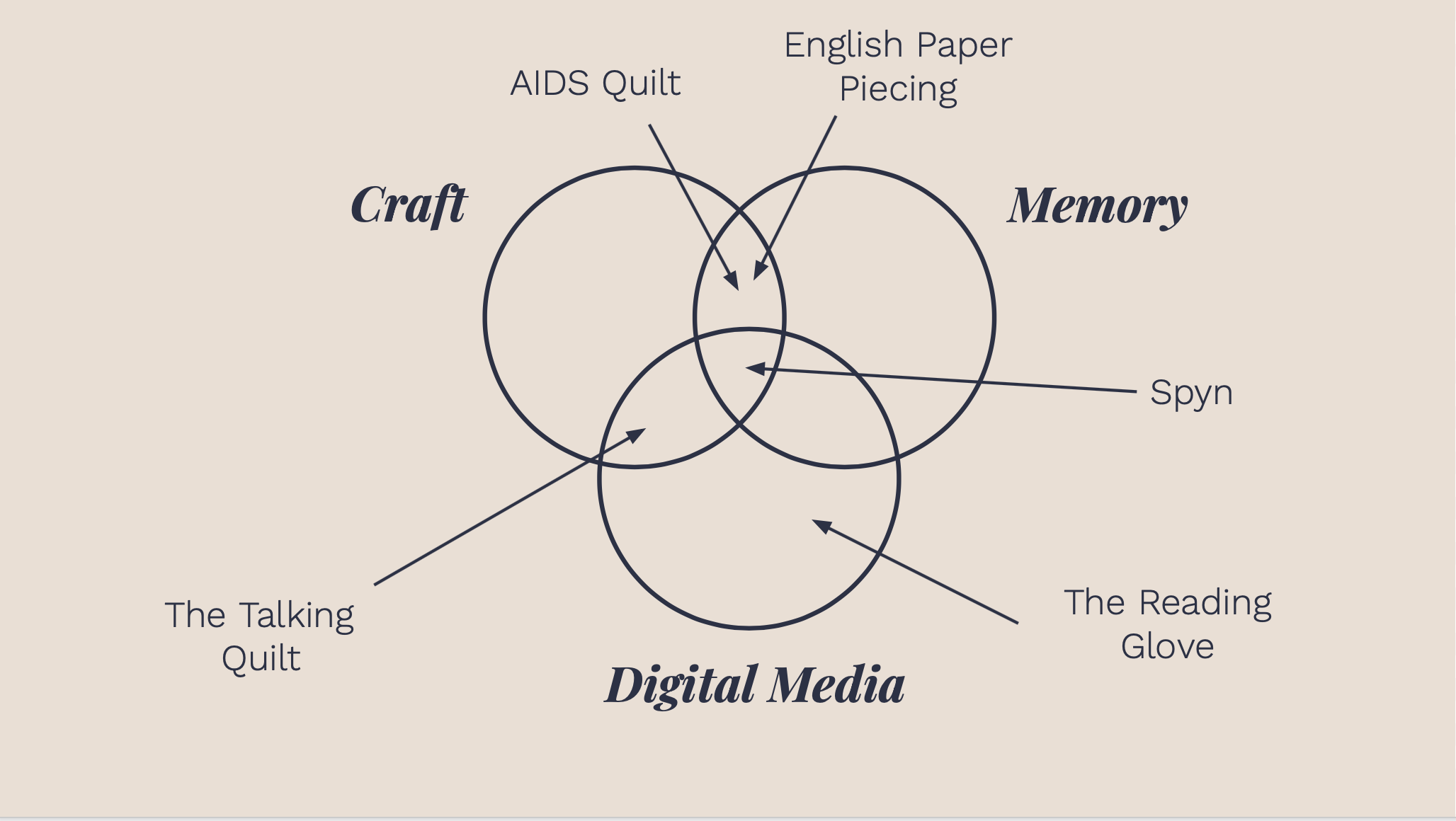

Craft as means to understanding